노인 고혈압의 치료

Treatment of hypertension in elderly

Article information

Trans Abstract

Whereas systolic blood pressure (SBP) continuously rises with age, diastolic blood pressure (DBP) gradually decreases after the age of 55 years. Therefore, hypertension in the elderly shows the pattern of isolated systolic hypertension. There is evidence on the benefits of controlling blood pressure (BP) in elderly patients with hypertension. The BP lowering effect has also been demonstrated in patients over 80 years of age with hypertension. The BP threshold for the initiation of antihypertensive drug treatment for older adults with hypertension is gradually decreasing. The antihypertensive treatment is recommended if, despite therapeutic lifestyle modifications, SBP ≥140 mmHg or DBP ≥90 mmHg in those aged 65-79 years old, and SBP ≥140-160 mmHg or DBP ≥90 mmHg in those aged ≥80 years old. Although there is no consensus on the target BP for older adults with hypertension, a target SBP of <130-140 mmHg and DBP of <80-90 mmHg are recommended. In older adults over 80 years of age with hypertension, the target SBP is <140-150 mmHg. When the dose of antihypertensive drugs is increased to reach the target SBP, DBP may decrease to less than 70 mmHg, but it should not be <60 mmHg. Thiazide diuretics, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, or angiotensin receptor blockers can be selected as the first-line drug for older adults with hypertension. Beta-blockers may be selected in case of compelling indications.

서 론

우리나라는 평균 수명의 증가와 낮은 출산율이 지속되면서 2017년에 65세 이상 인구 비율이 14%를 초과한 고령 사회가 되었고 2026년에는 21%를 넘는 초고령 사회로 진입할 것으로 예상된다. 고혈압은 심혈관 사건과 사망률을 효과적으로 감소시킬 수 있는 조절 가능한 위험인자 중 하나이다. 2019년 기준 우리나라 65세 이상 인구의 고혈압 유병률은 64% (남성 59%, 여성 68%), 추정 유병자 수는 495만 명(남성 196만 명, 여성 299만 명)으로 고혈압은 노인의 대표적인 만성 질환이다[1]. 하지만 노인 고혈압의 치료 시점, 적정 목표 혈압 등에 대한 논란은 최근까지 지속되고 있다.

이 종설에서는 노인 고혈압의 특성, 치료 효과, 치료 시점, 적정 목표 혈압, 치료 약물 등에 대해서 최근 임상 연구 결과와 여러 고혈압 진료 지침을 중심으로 고찰하고자 한다.

본 론

1. 노인 고혈압의 특성

좌심실 수축에 의해서 발생한 동맥파는 주로 혈관 직경이 작고 저항이 큰 말초 세동맥에서 반사되어 수축기 중기 이후 대동맥으로 되돌아오는데 동맥압은 진행파(incident wave)와 반사파(reflected wave)가 중첩되어 증폭된 맥파의 압력이다. 심장은 주 기적으로 수축과 이완을 반복하기 때문에 심장의 후부하는 말초혈관저항에 의한 정적 요소(steady component)뿐만 아니라 동맥의 특성에 의해서 결정되는 동적 요소(dynamic component)의 영향을 받는다. 심장의 동적 후부하(pulsatile afterload)는 대동맥의 특징적 임피던스, 반사파의 크기와 중첩 위치, 동맥계의 탄성도 등에 의해서 결정된다[2].

연령이 증가함에 따라서 혈관의 탄성 섬유가 감소하고 콜라겐 침착이 증가하는 혈관 노화가 진행되면 탄성(elastance)과 유순도(compliance)가 감소하고 동맥의 경직도(stiffness)가 점차 증가한다. 동맥의 경직도가 증가하면 진행파와 반사파의 속도가 빨라져서 반사파가 수축 중기에 중첩되어 대동맥 수축기압과 맥압은 증가하고 이완기압은 감소한다[3]. 연령이 증가할수록 수축기 혈압은 지속적으로 상승하는 반면에 이완기 혈압은 55세 이후 점차 감소하여 노인 고혈압은 고립성 수축기 고혈압(isolated systolic hypertension)의 양상을 보이게 된다. 그 결과 증폭된 대동맥 수축기압에 의해서 좌심실 후부하와 심근 산소 요구량이 증가하고 감소된 대동맥 이완기압에 의해서 관동맥 혈류는 감소하여 심근 허혈이 유발된다. 따라서 노인 고혈압 환자의 동맥 경직도 증가는 관동맥 질환, 심부전 등의 심혈관 질환 발생의 원인이 될 수 있다[4,5].

2. 노인 고혈압의 치료 효과

1990년대 초까지는 심혈관계 합병증 예방을 위해서 이완기 혈압 조절의 중요성을 주로 강조하였지만 90년대 중반 이후 이완기 혈압보다 수축기 혈압과 맥압의 증가가 심혈관계 합병증 발생에 더 중요한 역할을 한다는 연구들이 발표된 이후 수축기 혈압의 조절에 더 역점을 두게 되었고[6], 최근에 발표된 고혈압 치료 효과에 대한 연구는 주로 노인의 고립성 수축기 고혈압 환자들이 대상이 되고 있다.

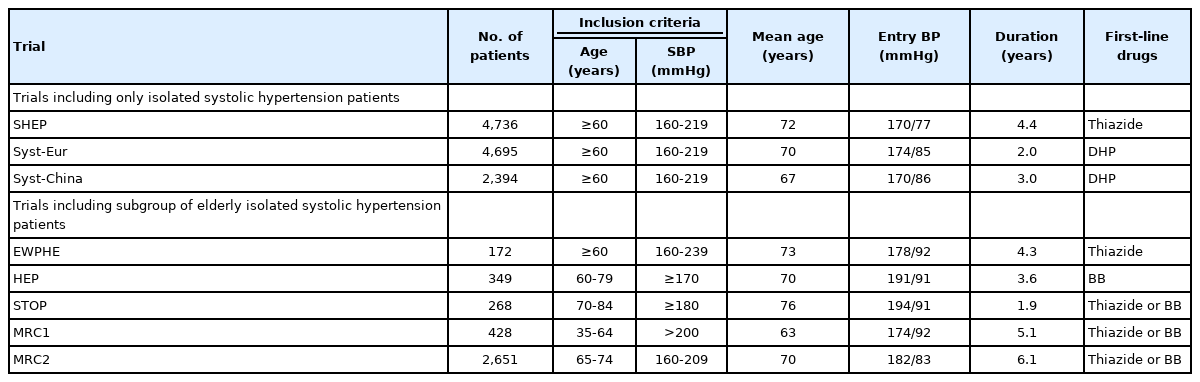

2000년 이전 발표된 수축기 혈압 ≥160 mmHg이고 이완기 혈압 <90 mmHg인 60세 이상의 고립성 고혈압 환자를 대상으로 한 8개 연구, 총 15,693명의 메타분석 결과가 발표되었는데 연구 시작 시점의 평균 혈압은 174/83 mmHg였고 연구 기간(중앙값 3.8년) 동안 치료군과 대조군 사이의 혈압 차이는 수축기 혈압 10.4 mmHg, 이완기 혈압 4.1 mmHg였다(Table 1) [7]. 치료하지 않은 대조군의 분석에서 초기 수축기 혈압이 10 mmHg 높으면 총 사망률과 뇌졸중의 비교 위험도는 각각 26%와 27% 증가하였다. 고혈압약으로 혈압을 조절하면 총 사망률, 심혈관계 사망률이 각각 13% (P =0.02)와 18% (P =0.01) 감소하였고, 모든 심혈관계 합병증, 뇌졸중, 관동맥 사건은 각각 26% (P <0.0001), 30% (P <0.0001), 23% (P =0.001) 감소하였다. 무작위 배정법이 사용되지 않은 1개의 연구 결과를 제외하여도 심혈관계 사망(16%), 심혈관계 합병증(25%), 뇌졸중(30%)의 예방 효과는 변함이 없었지만 총 사망률(10%) 감소 효과는 둔화되었다. 65세를 기준으로 강압 효과가 심혈관계 사건에 미치는 영향을 연구한 메타분석에서도 65세 이상의 노인 고혈압 환자에서 65세 미만의 환자와 동일한 심혈관계 사건 발생 감소율을 보였으며 65세 이상 고령 환자의 심혈관계 사건 발생률이 높기 때문에 강압 효과의 절대적 이득이 더 많았다[8].

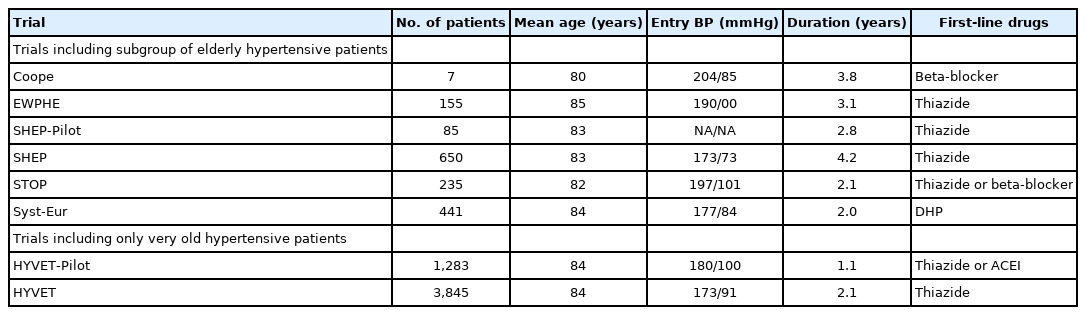

80세 이상의 초고령 고혈압 환자에게 강압제를 투약하여 사망률을 감소시킬 수 있는가에 대한 논란이 있었는데 일부 연구에서는 오히려 혈압 강하가 사망률을 증가시킨다는 결과가 있었다. 하지만 80세 이상의 초고령 고혈압 환자를 대상으로 한 Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET) [9]이 발표되면서 어느 정도 논란이 줄어들었다. HYVET에서는 수축기 혈압 ≥160 mmHg이거나 이완기 혈압이 90-109 mmHg인 80세 이상 고혈압 환자 3,845명을 대상으로 치료군과 위약군을 비교하였다. 목표 혈압은 150/80 mmHg였으며 치료군의 일차 고혈압약은 이뇨제인 indapamide였고 목표 혈압에 도달하지 못하면 안지오텐신 전환효소억제제인 perindopril을 추가하였다. 이 연구는 조기 종료되었는데 일차 종말점인 뇌졸중은 통계적 유의성 없이 30% 감소에 그쳤지만 사망률이 유의하게 21% 감소하였기 때문이다. HYVET을 포함한 8개의 80세 이상의 초고령 고혈압 환자 연구 결과의 메타분석에서는 총 사망률은 감소하지 않았지만 뇌졸중(35%), 심혈관계 사건(27%), 심부전(50%) 등은 유의하게 감소하였다(Table 2)[10].

3. 노인 고혈압의 치료 시점과 목표 혈압

노인 고혈압 환자의 이완기 혈압은 치료 전 이미 90 mmHg 미만인 경우가 대부분이기 때문에 수축기 혈압을 기준으로 약물 치료 시점과 목표 혈압을 결정한다. 2010년 이전에 시행된 노인 고혈압 연구는 치료 전 수축기 혈압 ≥160 mmHg인 환자들을 대상으로 하였고 대부분의 연구에서 연구 종료 시점의 혈압이 ≥ 140 mmHg였기 때문에 수축기 혈압 140-159 mmHg인 환자의 강압 효과는 확실치 않았다[11]. 또한 적극적인 강압 치료 효과를 연구한 Japanese Trial to Assess Optimal Systolic Blood Pressure in Elderly Hypertensive Patients에서 수축기 혈압을 140 mmHg 미만으로 유지하여도 140 mmHg 이상으로 유지한 환자에 비해서 심혈관계 사건 발생률을 감소시키지 못하였다[12]. 이러한 제한점과 근거 부족으로 인하여 2013년 유럽고혈압학회의 진료 지침에서는 생활습관 개선 노력에도 불구하고 수축기 혈압 ≥160 mmHg인 노인 고혈압 환자에게 약물 치료가 권고되었고 80세 미만이면서 고혈압 약물 치료에 잘 견딜 수 있는 경우 수축기 혈압 140-159 mmHg인 노인 고혈압 환자에서도 약물 치료를 고려해볼 수 있다고 하였다[13]. 미국의 2014년 Joint National Committee (JNC) 8에서도 60세 이상 고혈압 환자의 수축기 혈압 ≥150 mmHg인 경우 약물 치료를 권고하였다[14].

고위험 고혈압 환자의 수축기 목표 혈압을 140 mmHg보다 낮추는 것이 심혈관계 사건 발생 감소에 더 효과가 있는지 알아보기 위한 Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Blood Pressure (ACCORD BP) 연구가 2010년에 발표되었다[15]. 당뇨병 환자 중 심혈관계 사건 발생의 고위험군(평균 연령 62세)을 대상으로 수축기 목표 혈압 <120 mmHg (적극 치료군)과 120-139 mmHg (표준 치료군)을 비교하였는데 예상과 달리 수축기 혈압을 적극적으로 낮추어도(1년 후 평균 수축기 혈압 119.3 vs. 133.5 mmHg) 심혈관 사건 발생률, 총 사망률에 차이가 없었고 오히려 저혈압, 신기능 악화 등의 합병증이 증가하였다. 노인 고혈압 환자의 목표 혈압에 대해서 2013년 유럽고혈압학회의 진료 지침에서는 80세 미만인 환자는 일차로 수축기 혈압 140-150 mmHg를 유지하고 환자의 노쇠 정도와 내약성(tolerability) 등을 고려하여 140 mmHg 미만으로 낮출 수 있다고 권고하였다. 80세 이상의 고령의 환자는 신체적, 정신적 건강 상태가 좋다면 수축기 혈압 140-150 mmHg을 유지하도록 하였다[13]. JNC 8은 60세 이상 고혈압 환자의 수축기 목표 혈압을 <150 mmHg로 하였다[14].

하지만 2015년 Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial(SPRINT) [16]이 발표되면서 노인 고혈압 환자의 정의, 치료 시점, 목표 혈압 등에 대한 논란이 시작되었다. SPRINT는 고혈압약 복용 여부와 상관없이 수축기 혈압 130-180 mmHg이고 심혈관 질환이나 만성 콩팥병이 있거나 심혈관 발생 고위험군(발생 위험 1.5%/년 이상)에 속하는 50세 이상의 고혈압 환자 혹은 75세 이상의 고혈압 환자 9,361명(평균 연령 67.9세)을 대상으로 수축기 목표 혈압 <120 mmHg (적극 치료군)와 <140 mmHg (표준 치료군)를 비교하였다. 당뇨병과 뇌졸중 환자는 제외되었다. 1년 후 평균 수축기 혈압은 각각 121.4 mmHg와 136.2 mmHg였다. SPRINT는 조기 종료되었는데(추적 관찰 중앙값 3.26년) 적극 치료군에서 일차 종말점(심근경색증, 심근경색증 이외의 관동맥증후군, 뇌졸중, 심부전증, 심혈관 사망 등의 총합)은 25%, 총 사망은 27% 적게 발생하였다(Table 3). 75세 이상 노인 고혈압 환자 2,636명의 분석에서도 적극 치료군에서 일차 종말점은 34%, 총 사망은 33% 적게 발생하였다[17]. 노쇠 정도에 따른 분석도 하였는데 통계적 유의성은 없었지만 예상과 달리 노쇠 지표가 낮은 환자보다는 높은 환자에서 적극 치료의 효과가 더 좋은 것으로 보였다. 80세 이상 초고령 고혈압 환자 1,167명(평균 연령 83.5세)의 분석 결과도 동일하였다[18]. 하지만 인지 기능에 따른 비교를 하였을 때 인지 기능이 떨어진 초고령 고혈압 환자에서는 적극 치료의 효과가 없었다(Table 4).

그러나 SPRINT 결과에 대한 비평도 만만치 않다. SPRINT에서는 백의 효과(white-coat effect)를 최소화하기 위해서 가정혈압 측정과 유사한 혈압 측정 방법을 선택하였는데 피험자가 의료진이 없는 별도의 조용한 방에서 안정을 취한 후 자동혈압계를 이용하여 스스로 혈압을 측정하였다. SPRINT에서 사용된 진료실 자동혈압(automated office BP)은 일반적인 진료실 혈압에 비해서 최소 5 mmHg 이상 낮을 것으로 추정된다[19,20]. 또한 적극 치료군에서 표준 치료군의 평균 1.8개보다 많은 평균 2.8개의 고혈압약이 처방되었고 저혈압, 실신, 전해질 이상, 급성 신손상 혹은 신부전 등의 부작용 발생률은 높았다(Table 3). 비슷한 시기에 발표된 심혈관 사건 발생 중위험군(발생 위험 1%/년) 12,705명(평균 연령 65.7세)을 대상으로 한 연구에서는 혈압을 적극적으로 낮추어도(수축기 혈압 차이 6 mmHg) 심혈관 사건의 발생을 줄이지 못하였다[21].

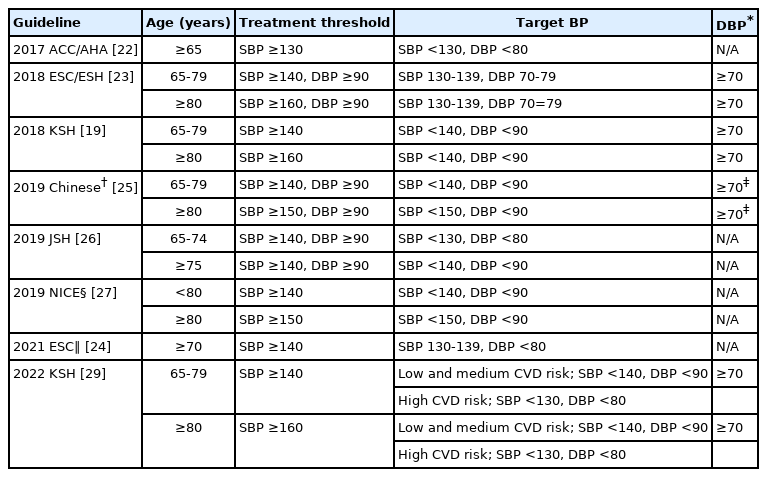

2017년 미국 고혈압 진료 지침에서는 SPRINT 결과를 적용하여 고혈압의 진단 기준을 수축기 혈압 ≥130 mmHg 혹은 이완기 혈압 ≥80 mmHg로 변경하였고 65세 이상 노인 고혈압 환자의 목표 혈압을 130 mmHg 미만으로 낮추었다[22]. 그러나 2018년 유럽 고혈압학회 진료 지침[23]과 대한고혈압학회 진료 지침[19]에서는 기존의 고혈압 진단 기준(수축기 혈압 ≥140 mmHg 혹은 이완기 혈압 ≥90 mmHg)을 고수하였다. 2018년 유럽고혈압학회 진료 지침에서 노인 고혈압 환자의 약물 치료 시작 시점을 65-79세는 수축기 혈압 ≥140 mmHg 혹은 이완기 혈압 ≥90 mmHg, 80세 이상은 수축기 혈압 ≥160 mmHg 혹은 이완기 혈압 ≥90 mmHg로 하였고 65세 이상 환자의 목표 수축기 혈압은 130-139 mmHg, 이완기 혈압은 70-79 mmHg로 수정하였다(Table 5) [23]. 2021년 유럽심장학회의 심혈관 질환 예방 가이드라인에서는 70세를 기준으로 목표 혈압이 달리 권고되었는데 70세 이상인 노인 고혈압 환자는 수축기 혈압 130-139 mmHg, 이완기 혈압 <80 mmHg로, 18-69세인 고혈압 환자는 수축기 혈압 120-130 mmHg, 이완기 혈압은 <80 mmHg로 부분 변경되었다[24]. 2018년 대한고혈압학회 진료 지침의 65세 이상 노인 고혈압 환자의 약물 치료 시점은 2018년 유럽고혈압학회 진료 지침과 동일하고 목표 혈압은 수축기 혈압 <140 mmHg, 이완기 혈압 <90 mmHg로 권고되었다(Table 5) [19]. 2018년 중국 고혈압 진료 지침의 노인 고혈압 약물 치료 시작 시점과 목표 수축기 혈압은 65-79세인 경우는 각각 140 mmHg 이상과 미만으로, 80세 이상인 경우는 각각 150 mmHg 이상과 미만으로 권고되었고[25] 2019년 일본 고혈압 지침의 노인 고혈압 환자 약물 치료 시작 시점은 수축기 혈압 140 mmHg 이상, 목표 수축기 혈압은 65-79세인 경우는 <130 mmHg, 80세 이상인 경우는 <140 mmHg로 권고되었다(Table 5) [26]. 고혈압 약물 치료에 대해서 가장 보수적인 영국의 2019년 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 가이드라인에서는 80세 미만 고혈압 환자의 약물 치료 시작 시점을 합병증이 없거나 고위험군이 아닌 경우 수축기 혈압 ≥160 mmHg, 합병증이 동반되었거나 고위험군인 경우 수축기 혈압 ≥140 mmHg로, 80세 이상 고혈압 환자는 수축기 혈압 ≥150 mmHg로 하였고 목표 수축기 혈압은 심혈관 질환 동반 여부와는 상관없이 80세 미만 환자는 <140 mmHg, 80세 이상 환자는 <150 mmHg로 권고하였다(Table 5) [27].

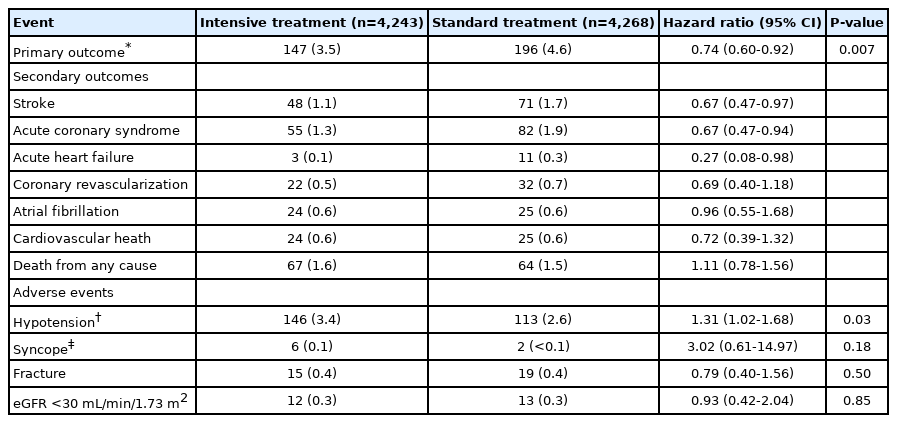

최근 중국인 노인 고혈압 환자 8,511명(평균 연령 66.3세)을 대상으로 적극 치료군(수축기 목표 혈압 110에서 <130 mmHg)과 표준 치료군(수축기 목표 혈압 130에서 <150 mmHg)의 효과를 비교한 Strategy of Blood Pressure Intervention in the Elderly Hypertensive Patients (STEP) 연구가 발표되었다[28]. 1년 후 평균 수축기 혈압은 적극 치료군 127.5 mmHg, 표준 치료군 135.3 mmHg였다. STEP 연구에서는 전자혈압계로 의료진이 직접 혈압을 측정하는 통상적인 진료실 혈압 측정 방법을 사용하였기 때문에 적극 치료군의 1년 후 평균 수축기 혈압은 진료실 자동혈압 측정 방법을 채택한 SPRINT의 121.4 mmHg와 차이가 없을 것으로 추정되었다[20]. 추적 관찰 기간(중앙값 3.34년) 동안 표준 치료군에 비해서 적극 치료군에서 일차 종말점(뇌졸중, 급성 관동맥증후군, 급성 심부전, 관동맥혈관재통, 심방세동, 심혈관 사망 등의 총합) 26%, 뇌졸중 33%, 급성 관동맥증후군 33%, 급성 심부전 73% 감소하여 동양인 노인 고혈압 환자에서도 수축기 혈압을 130 mmHg 미만으로 낮추는 것이 심혈관 질환 예방 효과가 더 좋다는 것을 보여주었다. 그러나 심혈관 사망이나 총 사망은 차이가 없었다. 적극 치료군에서 저혈압의 발생 빈도가 높았다는 것 이외의 다른 부작용 발생 차이는 없었다(Table 6) [28]. 2022년 대한고혈압학회 진료 지침에서는 SPRINT와 STEP 연구 결과를 반영하였는데 심뇌혈관 중저 위험도의 65세 이상 노인 고혈압 환자의 약물 치료 시점과 목표 혈압은 2018년 진료 지침과 동일하나 고위험도 노인 고혈압 환자의 목표 혈압은 수축기 혈압 <130 mmHg, 이완기 혈압 <80 mmHg로 수정 권고되었다 [29].

SPRINT와 STEP 연구가 무작위 배정된 근거 수준이 높은 임상 연구이기는 하나 그 결과를 노인 고혈압 환자에게 일률적으로 적용하는 것이 타당한가에 대해서는 비판적인 시각도 여전히 존재한다. 최근 80세 이상 노인 고혈압 환자를 대상으로 한 코호트 관찰 연구에서는 혈압을 <140/90 mmHg로 낮추면 오히려 사망률이 40% 증가했다고 보고되었다[30]. 비록 SPRINT 분석에서 노쇠 지표가 낮은 환자보다는 높은 환자에서 적극 치료의 효과가 더 좋은 것으로 보였지만[17] 노쇠가 심한 환자는 제외되었다는 제한점 때문에 그 결과를 일반화하여 모든 노인 고혈압 환자에게 적용하기에는 무리가 있다[31]. 노인 고혈압 환자는 같은 연령이어도 생체 나이는 다를 수 있고, 백의 효과가 잘 나타나며, 기립성 저혈압이 흔히 발생하고, 여러 기저 질환이 동반되어 있으며, 노쇠 정도에 차이가 있어서 일상생활 활동력이 떨어져 있는 요양시설 거주 환자에게 동일한 목표 혈압을 일률적으로 적용하기는 힘들다[32]. 노쇠한 노인 고혈압 환자는 혈압 감소에 대응하는 자동 조절(autoregulation) 능력이 떨어져 있고 동맥 경직도가 증가되어 있어서 혈압을 낮게 유지하면 신체 내 여러 장기에 저관류(hypoperfusion)가 발생하여 오히려 나쁜 예후를 갖게 될 수 있기 때문에 임상 시험 연구에서 얻어진 근거와 관찰 연구의 결과 사이에 격차가 발생할 수 있다[31]. 노인 고혈압 환자의 목표 혈압은 신체 활동 능력, 생체 나이, 노쇠 정도, 요양시설 거주 여부 등을 고려하여 개별화해야 하며 목표 혈압에 도달하기 위해서 고혈압약 용량을 증량하기 전에 백의 효과의 존재와 수축기 혈압 <110 mmHg의 기립성 저혈압 발생 유무를 확인할 필요가 있다는 의견이 제시되었다[32].

노인 고혈압 환자의 적극적인 목표 혈압에 도달하기 위해서 고혈압약을 증량하면 이완기 혈압이 매우 하강하여 오히려 심혈관계 사건이 증가하는 J-curve 혹은 U-curve 현상에 대한 주장이 있어왔다[33]. 안정형 관동맥 질환이 있는 환자(평균 연령 65.2세)의 5년 코호트 관찰 연구에서 수축기 혈압 120-129 mmHg와 이완기 혈압 70-79 mmHg를 각각 기준으로 하였을 때 수축기 혈압 ≥140 mmHg 혹은 이완기 혈압 ≥80 mmHg뿐만 아니라 수축기 혈압 <120 mmHg 혹은 이완기 혈압 <70 mmHg일 때 총 사망률, 심혈관 사망률, 심근경색증, 심부전에 의한 입원 등의 증가와 관련이 있어서 J-curve를 관찰할 수 있었다[34]. ONTARGET/TRANSCEND 연구의 사후 분석에서는 수축기 혈압 <120 mmHg 혹은 이완기 혈압 <70 mmHg와 심혈관 사건 발생 사이의 연관성이 관찰되었다[35]. 네덜란드 고혈압 환자(평균 연령 71.5세)를 대상으로 한 코호트 관찰 연구에서는 고혈압약을 복용해서 이완기 혈압 65 mmHg 미만이 되면 오히려 뇌졸중 발생이 증가하는 것으로 보고되었다[36].

그러나 J-curve 현상에 대한 반론도 만만치 않다. 첫째, 심혈관계 질환이 없는 환자를 대상으로 한 관찰 연구에서 수축기 혈압 110 mmHg, 이완기 혈압 75 mmHg에 도달할 때까지 혈압 감소에 비례하여 심혈관 사망과 뇌졸중 발생이 감소하였다[37]. 둘째, 심혈관 질환의 고위험군에서 표적기관 혈액 관류를 유지하기 위한 역치(threshold)가 높다는 주장이 있지만 입증된 바 없다[33]. 셋째, 관찰 연구 혹은 사후 연구 분석 결과이므로 치료 후 혈압이 낮은 환자는 이미 연구 시작 시점에 여러 기저 질환을 갖고 있는 고위험군이었기 때문에 심혈관계 사건 발생 증가하는 역인과관계(reverse causality)의 가능성이 있다[31,33]. 넷째, 낮은 이완기 혈압보다는 맥압의 증가가 심혈관계 사건 발생에 더 악영향을 미쳤을 수도 있다[33].

SPRINT 사후 분석에서 적극 치료군과 표준 치료군 모두에서 이완기 혈압 <68 mmHg인 환자에서 심혈관 사건이 증가하는 J-curve 현상이 관찰되었으나 적극 혈압 조절의 이득은 여전히 증명되었다[38]. STEP 연구 시작 3개월 후 이완기 혈압 <60 mmHg, 혹은 맥압 >60 mmHg인 환자의 분석에서 수축기 혈압을 적극적으로 낮추어도 심혈관 사건 발생이 증가하지는 않았다[28]. ACCORD BP와 SPRINT 연구 기간 동안 평균 수축기 혈압 <130 mmHg인 7,515명의 분석에서는 이완기 혈압 70에서 <80 mmHg 일 때 심혈관사건 발생 위험이 가장 낮았고 <60 mmHg인 경우 발생 위험이 46% 증가하였다[39]. 따라서 이완기 혈압이 어느 정도 떨어져도 수축기 고혈압 환자의 약물 치료를 중단하거나 감량할 필요는 없다는 견해가 지배적이나 수축기 혈압이 130 mmHg 미만으로 떨어지면 이완기 혈압은 60 mmHg 미만으로는 감소하지 않도록 주의가 필요하다[39,40].

2017년 미국 고혈압 진료 지침의 이완기 목표 혈압은 <80 mmHg이나 하한치에 대한 언급은 없다[22]. 2018년 대한고혈압학회 진료 지침[19]에서는 관상동맥질환이 동반되어 있을 가능성이 높거나 심비대가 있는 노인 고혈압 환자의 이완기 혈압을 가능하면 70 mmHg 미만으로 낮추지 않도록 하였고 2018년 유럽고혈압학회 진료 지침[23]에는 이완기 목표 혈압을 70-79 mmHg로 권고하였다(Table 5). 그러나 2021년 유럽심장학회의 심혈관 질환 예방 가이드라인[24]에서는 이완기 목표 혈압을 <80 mmHg로 제시하였지만 하한치에 대한 언급은 삭제되어 노인 고혈압 환자의 약물 치료 중 이완기 혈압의 하한치에 대한 공통된 견해는 아직 없는 실정이다.

4. 노인 고혈압의 치료 약물

기존의 고립성 수축기 고혈압 환자를 대상으로 한 대규모 연구들에서 일차로 사용된 강압제는 티아지드(thiazide) 이뇨제와 dihydropyridine계 칼슘차단제였다(Table 1) [7]. 젊은 고혈압 환자는 비교적 혈중 레닌치가 높기 때문에 안지오텐신 전환효소억제제나 베타차단제에 대한 반응이 좋지만 노인 고혈압 환자는 혈중 레닌 활성도가 낮고 체액량에 더 의존적이기 때문에 이뇨제나 칼슘차단제에 대한 반응이 더 좋다는 연구들이 있었다[41]. 또한 베타차단제인 atenolol과 안지오텐신 수용체차단제인 losartan 의 강압 효과를 비교한 Losartan Intervention for Endpoint Reduction (LIEF) 연구의 고립성 수축기 고혈압 환자(평균 연령 70세) 하위 분석에서 losartan 투약군에서 총 사망, 심혈관계 사망, 뇌졸중 등이 적게 발생하였다[42]. 뇌졸중 발생에 대한 LIEF 연구의 심층 분석에서 losartan의 효과는 65세 이상의 고혈압 환자에서만 관찰할 수 있었고 고립성 수축기 고혈압 환자에서는 뇌졸중 발생이 44% 감소하여 losartan의 효과가 더욱 뚜렷하였다[43]. Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial-Blood Pressure Lowering Arm에서는 심혈관계 위험인자가 있는 19,257명의 고혈압 환자를 대상으로 칼슘차단제인 amlodipine과 베타차단제인 atenolol의 강압 효과를 비교하였다[44]. 평균 연령은 63세였고 60세 이상의 고혈압 환자가 63%를 차지하였다. 목표 혈압에 도달하지 않으면 amlodipine 복용군에서는 안지오텐신 전환효소억제제인 perindopril이, atenolol 복용군에서는 이뇨제인 bendroflumethiazide가 첨가되었다. 이 연구는 5.5년 진행 후 조기 중단되었는데 amlodipine+perindopril 복용군에서 사망률 11%, 뇌졸중 23% 감소 효과가 있었다. 이러한 효과는 60세 이상의 고혈압 환자에서도 동일하였다. 이러한 근거를 바탕으로 2007년 유럽고혈압학회 진료 지침에서는 노인성 고혈압 환자의 일차 약제로 저용량 이뇨제나 칼슘차단제를 우선적으로 고려하도록 권고되었다[45].

그러나 고혈압약 종류별 심혈관계 질환 예방 효과를 분석한 메타분석은 다른 결과를 보여주었다. 관동맥 질환의 과거력이 있는 환자에서 베타차단제는 심혈관계 사건의 재발을 29% 감소시킨 반면에 다른 계열의 고혈압약은 15% 감소시켰다[46]. 고혈압약제 종류간 비교에서 칼슘차단제의 뇌졸중 감소 효과가 약간 우월하였지만 이뇨제, 베타차단제, 칼슘차단제, 안지오텐신 전환효소억제제, 안지오텐신 수용체차단제 등 5종류의 고혈압 약제는 혈압 감소 정도가 같을 때에는 모두 유사한 관동맥 질환과 뇌졸중 예방 효과를 보여서 특정 계통의 고혈압약에 국한된 우월성을 관찰할 수 없었다[46]. 65세를 기준으로 분석해도 고혈압약 종류에 따른 강압 효과의 차이도 없었다[8]. 2017년 미국고혈압 진료 지침에서는 베타차단제를 제외한 티아지드계 이뇨제, 칼슘차단제, 안지오텐신 전환효소억제제, 안지오텐신 수용체차단제 등 4종류의 고혈압약 중에서 일차 약제를 선택하도록 권고하였다[22]. 2018년 대한고혈압학회 진료 지침[19]과 2018년 유럽고혈압학회 진료 지침[23]에는 환자가 갖고 있는 적응증, 금기사항, 환자의 동반 질환, 무증상장기손상 등을 고려하여 티아지드계 이뇨제, 칼슘차단제, 안지오텐신 전환효소억제제, 안지오텐신 수용체차단제뿐만 아니라 베타차단제도 일차 약제로 선택할 수 있도록 하였다. 노인 고혈압 환자에서 베타차단제는 치료 이득에 대한 논란이 있어 특별한 적응증이 있는 경우에만 권고되었다[19]. 2019년 영국 NICE 가이드라인에서는 여전히 55세 이상의 고혈압 환자는 칼슘차단제를 일차 약제로 선택하고 칼슘차단제의 부작용 때문에 복용할 수 없거나 심부전 동반 시에는 티아지드계 이뇨제를 투약하도록 권고하였다[25].

결 론

연령이 증가할수록 수축기 혈압은 지속적으로 상승하는 반면에 이완기 혈압은 55세 이후 점차 감소하여 노인 고혈압은 고립성 수축기 고혈압의 양상을 보이게 된다. 노인 고혈압 환자의 혈압을 조 절하여 얻을 수 있는 이득은 분명하다. 80세 이상의 초고령 고혈압 환자의 강압 효과 또한 증명되었다. 노인 고혈압 환자의 약물 치료 시작 시점은 점차 낮아지고 있다. 생활습관 개선 노력에도 불구하고 65-79세는 수축기 혈압 ≥140 mmHg 혹은 이완기 혈압 ≥ 90 mmHg, 80세 이상은 수축기 혈압 ≥140-160 mmHg 혹은 이완기 혈압 ≥90 mmHg이면 약물 치료를 시작한다. 노인 고혈압 환자의 목표 혈압에 대해서는 여전히 일치된 견해가 없는데 수축기 목표 혈압은 <130-140 mmHg, 이완기 목표 혈압은 <80-90 mmHg로 권고된다. 80세 이상 초고령 고혈압 환자의 수축기 혈압은 <140-150 mmHg를 목표로 한다. 수축기 목표 혈압에 도달하기 위해서 고혈압약을 증량하면 이완기 혈압이 70 mmHg 미만으로 감소할 수 있는데 60 mmHg 미만으로 떨어지지 않도록 주의해야 한다. 노인 고혈압 환자의 일차 약제로 티아지드계 이뇨제, 칼슘차단제, 안지오텐신 전환효소억제제, 안지오텐신 수용체차단제 중에서 선택할 수 있으며 베타차단제는 특별한 적응증이 있는 경우에 만 일차 약제로 사용한다.

Acknowledgements

이 논문은 2022학년도 제주대학교 교육·연구 및 학생지도비 지원에 의해서 연구되었다.